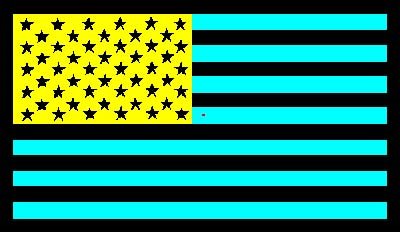

My favorite model for stress reduction comes from a visual perception trick using the American Flag. Try this exercise with me and I promise you’ll learn some powerful mind and body insights you probably weren’t aware of before.

Get a white piece of paper or choose a white wall in your room. After you stare at the black dot in the middle of the flag for 1 minute, you’re going to look back to the white paper or wall. And when you do, make sure to blink a few times….

Ready?

Now go. I’ll wait.

Wasn’t that like ah-mazing, life-changing stuff?! Ok, so you saw the American flag in red, white and blue. Big surprise.

But WHY it happens is what’s so revealing to me. In 1878, after-images were explained by German physiologist Ewald Hering through the opponent-process theory. Basically, if you look at the colors, its wavelengths excite the corresponding neurons sensing them in your eye.

Now get ready here it comes…

Soon after the neurons become excited, opposing neurons and chemicals reverse this process. The opposing neurons and chemicals inhibit the excited neurons and the inhibiting neurons, in turn, become more and more active over time.

And when you finally look over at the white wall, the opposing colors are dominant in your neurology… blue becomes red… black becomes white… yellow becomes blue.

Presto chango!

3 SOMEWHAT SURPRISING LESSONS FOR STRESS REDUCTION

Newton’s Third Law stated, “for every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction.” And I’ll be damned if he wasn’t right.

But it’s not just physics. The same holds true when it comes to our basic function. If we flex our bicep, what stops us from flexing our tricep? If we move our right leg forward, what stops us from engaging our right glutes and quads at the same time? And what would happen if we tried to step forward with our right leg and ALL muscles in that leg engaged?

Without the ability to stop opposing muscles, we wouldn’t be able to walk or move. Not in any coordinated way at least, because motion requires a single directional force and when another force pushes in the opposite way, movement stops. The effort is still there, but the movement forward isn’t.

If our bodies evolved without the ability to oppose, or inhibit, our stimulated neurons then we wouldn’t be able to see either. Every color we visually sense has a component of inhibition so that we can see the next color. Every rose we sense is then inhibited so that we can smell the steaming garbage that inevitably comes next.

And every THOUGHT that fires a series of neurons in our brain also fires a series of inhibiting chemicals so we’re allowed to think our next thought….unless it’s Taylor Swift – then it’ll be in your head forever. Sorry.

When the nervous system loses it’s ability to inhibit in any part of the body, it can lead to many disorders like Epilepsy, Tourette’s, Parkinson’s, or Cervical Dystonia which I wrote about before.

Just like you can’t listen to beautiful music without the silence between the notes, the same must happen internally for us to have any coordinated response. Inhibition happens on a neurological and chemical level and it evolved in parallel with all our sense, motor and thought function from the time we were little protozoan that once depended on a single, slimy tail to move left and right so we can swim.

It’s part of the foundation of our ability to do anything. Simply put, without the ability to stop, our life can’t move forward.

Lesson 1: Use Physical Inhibition For Stress Reduction

We’re all ruled by fears and desires…but their initial spark always starts with a thought. Without the fear, without the desire, there is no chain reaction that follows.

And if you’ve been following the logic so far, then you understand thoughts are inhibited at the neural level too and this is done regularly and automatically throughout the day.

But is there a way to consciously control this? The (very) short answer is yes.

In 1958 a dedicated follower of Freud revolutionized our understanding of managing the fear response with his book Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition. Building on decades of his own research as well as others, Dr. Joseph Wolpe began what would become modern behavioral research.

For him, reciprocal inhibition isn’t about the emotional suppressions Freud talked about but rather a simple mechanical understanding of learned behavior at the basic neurological level. Dr. Wolpe also called it systematic desensitization but it’s been given other names since then such as de-conditioning, counter-conditioning and finally exposure therapy, which is most popular today.

When Dr. Wolpe treated patients of any fear trigger, the first step was always the training of progressive relaxation. Once the patient was very relaxed, he had them imagine the fear trigger in various contexts, gradually exposing them more and more mentally. Over time, the fear response was desensitized, curing over 80% of his patients from neurosis.

Almost all successful treatment of fear therapy now practiced involves a conditioning process linking the main fear stimulus to a known counter response.

Dr. Wolpe and other scientists found there were physically reliable ways to elicit an oppositional response to fear such as relaxation, self-restraint, confidence, and even sexual arousal (!). So if you’ve long suspected that furiously jacking off was an appropriate response to your fear of public speaking, then rest easy dude because you were totally right about that. Just don’t do it while you’re speaking in public.

Interestingly, eating was also found to be another oppositional response to fear. Since we’re usually not being chased by a bear when we’re eating, the body has evolved to understand that we must be safe from any dangers if we’re able to take time to eat and it automatically shuts down neurological defensive systems to aid the digestion process, which takes a large amount of our energy. Eating relaxes us.

This might explain why so many of us reach for that late night cheese snack when faced with anxious feelings of tomorrow’s presentation. And if we’re stressed enough, our digestion may slow enough so we lose our appetite.

Many of our fears and anxieties are entangled with bad eating habits simply because it’s a reliable way to sooth ourselves… but eating celery can do the same job.

But on the off chance you DON’T want to furiously yank Mr. Thriller to overcome your fear of public speaking, here’s a list of ways to use your body for stress reduction now:

- Use deep diaphragmatic breathing to slow your pulse rate and respiration

- Lie down in semi-supine position and practice progressive relaxation on your own or with an audio guide for 20 minutes

- Eat a healthy snack

- Or eat lunch and then lie down to practice progressive relaxation

- Tense your muscles as much as possible for 30 seconds then release

- Practice speaking, moving and smiling confidently

- Practice releasing muscle tension on each exhale. It should feel like the breath falls out of your body without hinderance.

- Move more slowly or decide to pause for 1-3 minutes

- Exercise

You don’t have to drink alcohol, take sleeping pills or take anxiety drugs to relax. All those things are just forms of tranquilizers. That’s why they’re called downers.

And you don’t have to spend a lot of money to go on long vacations to relieve stress. You can learn to consciously relax your body and therefore your mind, right now.

With enough conditioning to the chosen relaxation response, our fear becomes altered at the neurological level. Eventually, the fear links in the brain goes to sleep and can remain dormant indefinitely. Viola! Fear is unlearned…and that terrible thing that happened to you when you were 6 years old? It doesn’t matter.

Suck it Freud!

Lesson 2: Use Mental Inhibition For Stress Reduction

In the late 1800’s, a Shakespearean actor struggled with a chronically hoarse voice, which no doctor could diagnose or cure. After a long struggle of self-observation and experimentation, F. Matthias Alexander came to an unsettling but clear conclusion: his voice issue was based on his desire to speak.

When he wanted to speak, he noticed a subtle response began, similar to stage fright. Except it was a habit where anytime he decided to speak at all, his head pulled back, his larynx would be depressed, breathing constricted and the airway squeezed.

But the approach he developed to cure it was a slightly different than Dr. Wolpe. Alexander concluded, “it would be necessary for me to make the experience of receiving the stimulus to speak and of refusing to do anything immediately in response.” In this case, stimulus = desire.

So his desire to speak is what interfered with his speaking. That desire led to an unconscious and automatic physical habit that prevented his efforts – and while he couldn’t prevent the physical reaction, he could prevent his initial desire.

In other words, he’d think about speaking – and then he’d immediately desire NOT to speak.

Can an opposing desire really inhibit another desire? I pondered this question for quite a while, spoke with a few experts and did my own research before reaching my own conclusion: yes it can.

Alexander’s technique relied greatly on this approach and ultimately cured himself with it. And like Dr. Wolpe, he also relied on similar methods of progressive relaxation along with incremental exposure to inhibit his unwanted speaking habits over time.

So both Alexander and Wolpe maintained that unwanted desires and fears should be systematically desensitized through a physical and mental approach. Because they’re both irrevocably linked.

What about inhibiting anger? Even before Sir Issac Newton, the ancient Stoics developed practices that fit this model nicely and flies in the face of Freudian psychology.

Instead of searching your childhood for your source of chronic anger and expressing your repressed emotions with a psychoanalyst until a catharsis “frees” you, Seneca believed in using reason to tame the savage beast.

To him, anger was a temporary insanity that exists as the desire to punish. And if an angry woman finds nothing to repay her suffering, then she’s likely to turn on herself to satisfy her anger’s desire to destroy something.

Seneca reasoned that anything useful that’s motivated by anger is better done without the impulsiveness of anger. Even the hunter doesn’t kill out of anger, but with careful deliberation. Likewise, the warrior doesn’t kill his enemy out of hatred but to simply defend his homeland.

“What are we to say to the argument that, if anger were a good thing it would attach itself to all of the most noble men? Yet the most irascible of creatures are infants, old men, and sick people. Every weakling is naturally prone to complaint.”

Through a list of reasoned arguments against the case of anger’s usefulness, Seneca seeks to install in his followers the desire to not be angry.

Rather than working to discover the origin of your anger and the reason it started, Stoics didn’t care why you were angry… the only cared about why you SHOULDN’T be angry. In fact, Seneca detailed so many reasons against it that it filled a whole book.

And before there was Seneca, Buddhists taught that by practicing compassion for others and yourself, anger couldn’t exist simultaneously. So their prescription for anger was to practice it’s opposing emotion of compassion because the “light” of compassion would cast away anger’s “darkness”.

Other parallels in Buddhism exist with Stoicism, such as the practice of patience, non-striving and equanimity (indifference to the Stoics). Now I don’t want to gloss over thousands of years of philosophy and psychotherapy here… but I’m going to gloss over thousands of years of philosophy and psychotherapy.

So here’s a summarized list of healthy oppositional desires you can practice, taken from Buddhism, Stoicism, Wolpe and modern research for stress reduction:

- Nonjudgmental curiosity

- Self-Compassion and compassion for others

- Gratitude or Altruism

- Patience, Letting Go or Non-Striving

- Equanimity, Indifference or Non-Attachment

- Contemplating the negative consequences of undesired behavior and the many benefits of positive habits to develop wanted motivation

- Desire to not desire (separate from the above as specific to a trigger)

- Contemplate your desired identity and the pride you’d feel with new thoughts, actions or lifestyle (identity shifts are needed for significant habits)

- Imagine a jug of warm oil being poured from the top of your head to through the bottoms of your feet, with each muscle it touches, imagine tension melts away

- Visualize a peaceful scene by the beach or a lake at sunrise or sunset

Echoing Buddhism, Stoics also recommended practicing happiness even as you feel anger. Seneca advised smiling, speaking softly and kindly to others in an effort to reverse dangerous passions. He recommended his students slow down and take a long pause before proceeding in a hasty or rash manner.

As we know today, acting in a happy way can send similar neurological signals to the brain and affect our moods positively. Today’s scientific research has well established the mind-body link. It’s no magic bullet but it’s another tool in our arsenal that we can use to directly or indirectly take power back in our hands.

You can even practice desires as intention throughout the day. Even if you don’t change anything you do, having a new intention for the hour, day or week sets a new direction for your thoughts. Those thoughts change how you feel and it influences your relationship with whatever you’re doing.

What did philosophers mean to “live like it’s your last day on earth”? Sorry to break the news, but it’s not about spending all your money on hookers and champagne. It’s a mental trick to develop gratitude (…that’s sustainable). And it makes it less likely that you’ll waste your time on meaningless tasks.

Take control of your daily focus today. Pick any of the above to practice and see what happens.

Lesson 3: Use Benchmarking For Stress Reduction

Did you ever wish you could wave a magic wand and have the ultimate emotional mastery to be completely calm, fearless and happy no matter what happens in your life or how bad it gets? If you get easily stressed like me, it sounds impossible.

But several researchers have proved something like that is possible, using fMRI results. In his book, Matthieu Ricard who’s dubbed the “happiest man in the world” presents Richard Davidson’s data on prefrontal cortex activity.

While there’s no center of happiness in the brain, people with dominant activity on the left side of the prefrontal cortex were associated with positive emotions such as joy, enthusiasm, altruism, and compassion. But those with a more active prefrontal cortex on the right side of the brain experienced more anxiety, fear, and feelings of unhappiness in their brain scans.

But the most interesting fMRI results found that the brain activity of practiced meditators was significantly higher in the left prefrontal cortex while they were meditating on compassion. In fact, the “activity in the left prefrontal cortex swamped activity in the right prefrontal (site of negative emotions and anxiety), something never before seen from purely mental activity.”

Want even more impressive research?

One of the top emotion scientists, Paul Ekman, studied thousands of people’s micro-expressions to determine how much control we really have over the startle response. Along with researchers at the University of California, they simulated a gunshot sound going off beside the ear, which they considered “the maximal threshold of human tolerance.” (sounds fun!)

He then monitored their body movements, pulse, perspiration, and skin temperature. Hundreds of subjects were told they’d hear a loud explosion within 5 minutes and were asked to suppress the natural startle response to their best ability and if possible, to the point of being imperceptible.

Previous research established elite police sharpshooters as the best benchmark. Their experience of firing guns every day was helpful exposure to this end – but it still wasn’t enough to stop them from flinching.

But do you know who could? Meditators.

The most successful were experienced meditators that practiced open presence awareness during the test. With one particular meditator, while there was an increase in pulse, perspiration and blood pressure, not one muscle moved.

With some astonishment, Ekman observed, “when he tries to repress the startle, it almost disappears. We’ve never found anyone who could do that. Nor have any other researchers. This is a spectacular accomplishment. We don’t have any idea of the anatomy that would allow him to suppress the startle reflex.”

This is God-like control.

But according to the subject, he wasn’t trying to actively control the flinch reflex, he described it as resting in the present moment where the bang simply occurs as if “I were hearing it from a distance.”

In other words, by practicing open awareness, his focus wasn’t attached to any one thing and he was able to accept anything that arose in his awareness with equanimity.

While these are all impressive feats of mind-body control, the point I want to make is that you can’t just decide to meditate one day and suddenly command God-like resistance to fear, anxiety or anger. It takes years of practice.

Our neurology tends to betray our pursuit of happiness. For survival reasons, our brains have evolved with a negativity bias that makes us overly responsive to real or imagined perceived threats. And the key in that statement is perceived. It doesn’t happen overnight but by now you know there are many ways to balance, neutralize and reverse the natural gravity of our fears and desires.

Those who experience positive feelings of calm, love, contentment, laughter or compassionate altruism, are less likely to be stressed when things don’t go their way. Practicing calm is cumulative. If you do it enough it becomes your natural baseline state.

Today’s neuroplasticity research backs this claim. If you operate in a world where you often feel anxious, worried and stressed out, you become more and more likely to get stressed out when things go wrong.

Research has shown that negative emotional responses can linger in the body long after the events that trigger them. Sometimes for hours, even days. And if the alarm bells in your body are still ringing, the alerted mind becomes ready to spot any potential dangers, making it more likely to interpret smaller threats as greater than they really are – even if imagined. These are called associative triggers.

Our preexisting state of calm or stress alters the threshold that any new trigger will develop.

This is a fancy way of saying that when you’re alone at night watching a horror movie, those scary sounds that convince you a trained murderer is creeping in your house are the secondary triggers. If the fear is strong enough or if it happens enough times (or both), then any similar sounds can become permanent triggers for you, even without the scary movie.

The stronger the fear, the higher the state of alert your body will be and the more associative triggers may develop. For those with chronic pain, where there’s always alarm bells ringing, social anxiety is typically a secondary trigger. In a world where everyone has at least some insecurities, any imperceptible slight or gesture can become cause for alarm.. until eventually, any interaction causes overwhelming fear and anxiety… which of course, sets the stage for even more chronic pain.

As more and more triggers develop, the world of pain becomes bigger and bigger. People who live in a state of chronic fear or anxiety are living in a shrinking world of pain.

It’s not hard to see we all tend to live smaller than we really are. But that’s why I’m here to tell you that it’s important to manage your baseline of comfort. You can take control of your fear response, counter it and push back. Even if you don’t know what’s causing your fear, you can still set yourself up for success.

Both physically and mentally, the best defense is a good offense.

Interestingly enough, the ancient stoics also developed a similar therapy, called practicing poverty. They would imagine losing a lost one, losing their fortunes, losing their health or anything they considered dear in their lives. The key is that they practiced poverty before it happened.

Not only did it help them be more grateful for what they had, but when misfortune struck, it wasn’t completely unexpected to them. It acted like a vaccine against sorrow. In many ways the mind is no different than a muscle.

Seneca told his followers that you should train your mind like an athlete trains his body. To be an olympian, an athlete trains his muscles before the games and seeks sparring partners that will not go easy on him so he can refine his skill.

As you get used to feelings of calm on a daily basis, it becomes your new benchmark of experience. That new benchmark makes smaller “disturbances in the force” that much easier for you to see and manage right away. If you’re an investor and the volatility index is averaging 10% for the past year but jumps to 25% one day, you better believe you’ll notice it right away.

That’s the power of benchmarking.

It brings more awareness because you become more sensitive to disturbing thoughts and feelings you may have been numb to before. It’s a positive feedback loop.

If you’ve ever trained physically for a long time and then stopped suddenly, you know how different your body feels after a short period. And when you miss feeling strong, you’re likely to go back to training…but you’d never know how weak you were if you weren’t so fit at some point, right?

When All Else Fails, Stop Everything!

This is related to everything before so it’s not really a fourth lesson. But it deserves extra focus. It’s the reason meditation is usually done sitting or lying still. Because when the muscles stop or relax, the mind usually follows. So give yourself a break.

When I was a broker, the top salesman in the company used to always walk back and forth in the hallways all day talking into his headset, until one day I asked him “why do you like to walk so much?” He told me, it helps him think.

Yes, moving helps us think. But if you want to stop thinking, then stop moving. Slow down, pause, close your eyes. The less stimulation, the easier it will be to settle your mind.

Have you ever seen parents who can enjoy eating a strawberry but to their kids, eating strawberries might as well be like eating cardboard paper? It’s because those kids are used to eating candies, chocolates and coca colas that have ten times more sugar than a stupid little strawberry. Their tongues are desensitized.

Our thoughts work the same way. When we slow down and stop, our minds calm down. Each thought is like a drop that ripples through the surface of a lake. But if enough time passes and there are no ripples to disturb the water, then the surface settles and becomes like a mirror, reflecting each moment without distortion… without the stories in our heads.

Given time, our senses reset and so does our nervous system. The constant inner dialogue we all have that’s prone to negative rumination eventually fades into the distance so we can see what’s in front of us anew. We can smell the proverbial rose and appreciate it better.

Some people turn to extremes like skydiving, skiing black diamonds or rock climbing to get out of their heads because it demands all of their focus. But if that’s the only way you can be focused in the present then the beauty of everyday life is passing you by.

Like a drug addict chasing the dragon, more and more sensation is required just to feel anything. Your minimum baseline of sensitivity grows ever higher and higher until numbness feels comfortably normal.

You don’t have to drop extreme sports to be mindful. My point is that it’s what you do every day that counts. It’s the string of little moments, the subtle sensations of life that predestine your resilience to handle stress and anxiety. You might think they don’t matter but they do.

You can pause or stop yourself anytime during the day to stop unmanageable feelings from developing and experience them with courage. Then you can work on calming your body and mind using any of the methods above.

In mindfulness, this is sometimes called the sacred pause. It’s considered a spiritual act because it allows us to discover ourselves and move beyond habitual thought. It’s the first step in acceptance that tells our brains “this isn’t a threat to me” and creates a space for increased awareness and calm.

Sometimes pausing is the hardest thing to do but that’s when we often need it most. That’s when we feel most out of control and in the grip of “dangerous passions.” Our ability to stop drives a wedge between our initial thoughts and the feelings and actions that might follow it. It breaks the cycle of reaction and puts you back in control.

***

As someone who lives with chronic pain, I’m far from an olympian mentally or physically, but I practice progressive relaxation twice a day. In the morning, when my body is most relaxed, I take advantage of this time in bed to mentally scan my body for any tensions and practice inhibiting the muscles as deeply as possible. After about 20 minutes, my musculature usually settles into a relaxed state and the calm carries over as I start the day.

Between breakfast and lunch, my body is usually starting to freak out again and I can feel the fear starting to grip around my mind. I then lay on the ground with a couple books under my head for another 20 minutes of progressive relaxation. I scan my body for tension, slowing my breath on each exhale and reset my baseline again.

I’d love to tell you this fixes everything for the rest of the day, but it doesn’t. What it does do for me, however, is prevent a very bad day from happening. It prevents my body from becoming an uncontrollable muscular pretzel and it prevents my inner mind from screaming “I CAN’T HANDLE THIS SHIT FOR ANOTHER SECOND WTF!?!” …before crawling into bed with my microwavable heating pad (and ideally with my adult sized carebear).

That’s what used to happen as soon as I woke up and grew increasingly more likely the rest of the day. That was my old baseline. That’s how I lived for many months. But now I kill the monster while it’s small.

And that’s how it is with physical and mental stress. If you want to be less susceptible to fear, anxiety and stress then you have to train your body and your mind against it.

I rotate various methods of meditation depending on how I feel. Doing it reduces accumulating stress and provides a backstop against anything that might have happened during the day or my own inner chatter. It resets me neurologically no matter what happens.

And like the Stoics and Buddhists, sometimes I practice compassion for others and imagining what it would be like to lose them. It increases my gratitude for those I love and I’m more likely to be present. (Self-compassion comes in really handy after a night of heavy drinking and the tsunami of shame and regret that follows.)

So now I think I’ll take my own advice and stop here. And like the ending of a Jerry Springer episode, here’s my final thought:

***

You can train your mind today to be stronger and calmer tomorrow. But train every day if you want to build a foundation strong enough to weather all the earthquakes, storms and forest fires that are an inevitable part of our lives. We can’t always prevent bad things from happening to us but there are many ways we can change our relationship with them.

When it comes to stress reduction, set yourself up for success. No, we can’t stop ourselves from feeling the initial feelings of fear, anxiety and stress. That’s just being human. But we can build calm on top of it. We can use it to teach our minds and bodies to be stronger in the face of it and build up our courage, brick by brick.

It may not happen overnight. It may take days, weeks, months or even longer. But with enough time and practice, we can reclaim our inner peace. After all, it’s in our very nature.

The rest is up to us.

Until next time… take care of yourself. And each other.